Autism Anglia: The Doucecroft School

You have to treat people equally, that's the bottom line.

Space. It is the most essential concept for children to be able to grow up and develop freely. What is space anyway? I think and believe that it is above all a feeling, a sensation. My four children grew up in the cabin of a sailing ship, on 12 square metres. They were always playing and rarely arguing.

This ship was our home and our income. From April to October, we sailed the Baltic Sea with passengers. We lived on board so the children did not go to school during those months. They were taught on board, with the permission of the school attendance officer, because boarding school was not an option for us.

I remember that there was a dispute with the medical nursery where Cato went when she turned 4. They were afraid that 'the treatment' would be interrupted too long if I took her to sea for two months. I knew one thing for sure, life on board was not harmful for the children.

They were lovely girls who worked there and they admitted wholeheartedly that Cato had grown enormously after her sea voyage and had actually deteriorated in the months following her arrival at the medical nursery.

I have another memory. There was a passenger who travelled with us every year and who used to look in through the small windows of our cabin. He once said to me: 'It's incredible, your children are always playing. I live in a big house and my children are always fighting.’

Space is freedom and freedom is space. Space is not necessarily a large empty surface, freedom is not necessarily a few hours without assignments. The concepts are inextricably linked. You feel freedom in your head because you feel the space to feel free.

In the Netherlands, children with autism are not given the space to feel free at school.

They have to go to school, they have to behave like other children, they have to sit still while they cannot, they have to learn while they are overexcited, they have to play in the square while they are afraid of the crowd. They have to. When they can't do it anymore, they have to go into treatment to learn how to do it, have to be able to do it. And then they have to go back to school. Until they really can't do it anymore. And then they are allowed to stay at home and they are allowed not to belong. And they are allowed to feel that they have failed. And then they are often only fourteen years old.

The whole process of growing up, the most receptive time of a person's life, was for these children in captivity. The cage was their head. The jailer was the system, the government, the school attendance officer, Child Protection, the judge. I leave it to specialists to explain honestly and clearly how such a childhood affects the rest of those lives.

Why is this happening? Because in most countries, there is a commitment to inclusion. Everyone has to belong.

Schools are by definition not suitable for children with autism because of the legal frameworks and the way they work. This also counts for special schools.

However, a lot of government money goes to schools to achieve inclusion within the framework of the law and so children with autism must attend, otherwise the investment is for nothing. That is why children are pushed back into schools until they drop out.

In the Netherlands, the drop outs end up at home on the couch, gaming in the bedroom or suicidal in an institution. And then some of them, will end on the street whoring for shelter or as 'the confused person' mentioned in the newsbroadcast or in crime as a drug runner or worse.

In England, there are schools that can make a difference.

In Colchester, Essex, there is a school for children with autism. The Doucecroft School of Autism Anglia has room for 64 pupils. It is not an inclusive school. It is an island of safety. Children who go here are given the space to feel safe, but even in England it is not a given truth that a child with autism will have this opportunity. ‘Some children have seen many schools before they come here and then they are sometimes only seven years old!’ the Headteacher Louise Parkinson explains. Here parents also have to fight for a safe place for their kids.

At the Doucecroft school children get education and care. This is a construction that is forbidden in the Netherlands because of an idiotic law that stipulates that the school money that is available for each child, can only go to a school. The building must also be marked as a school building.

Here in the UK apparently it is possible, care and education under one roof. And what a roof!

The Doucecroft School is not one building. It looks like a kind of mini-village. There is room for children between the ages of 6 and 19. (Officially from the age of 3, but this age is not present at the moment).

In the UK, schoolchildren are divided into 'Key Stages' (KS). KS1 is from 6 to 8 years, KS2 is from 8 to 11 years, KS3 is from 11 to 14 years and KS4 is from 14 to 16 years. As in Spain, all children in the UK complete at 16 the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE). This can be followed by two years of college in preparation for university.

In mainstream schools, the Key Stages are divided into schoolyears but at Doucecroft School, the Key Stages are divided into groups of children who fit together. Key Stage 4 is called Transition here. It does not necessarily lead to a diploma but they work towards a conclusion. That can be an exam or sheltered work, an internship or a subsequent education through a preparatory year and sometimes college.

Sam Lawrence (assistant headteacher) gives me a tour. She leads me around the grounds and I notice that she neatly follows the zebras that have been placed between the buildings. Setting a good example, that goes for every educator. We meet two children who are on their way to the garden for an assignment. Ordinary children. They suffer from autism otherwise they wouldn't be here, but they are ordinary children. And at this small moment, I realize that very strongly. They look so happy and excited. Sam greets them. ‘What are you two up to?’ she asks cheerfully. I don't hear the answer but Sam waves them over and wishes them good luck. 'No,' she replies to my question, 'the doors aren't closed here. Children are allowed to walk around freely. If we don't quite trust it, with the little ones for example, an assistant follows them but they are free to go outside.'

The different Keystages have their own building. Each Keystage has several groups of up to four pupils and in the classes I saw three supervisors. A teacher, an assistant and a learning support assistant, Sam explains to me. ‘The assistant is the official replacement when the teacher is not there.’ There is a lot of individual attention for each child.

The Transition groups are a bit larger and can do with one or two teachers. After all, these pupils have been learning for some years.

There is a quiet room in every building. Some classes have their own quiet room and sometimes two classes share one. Because in one class there are children who are very sensitive and in other classes they can handle a bit more. Classes also look different. Some children are good learners and they share a room that is designed for study. While in another group there is more emphasis on discovering with the hands, which is shown from the materials and furnishings.

Sam also shows me the building where the therapeutic department is located. There are all kinds of therapies, such as music therapy and animal therapy. There is a therapeutic/sensory gymnasium, there are consulting rooms. I meet the sports teachers there. ‘They excel at coming up with all kinds of activities and games that have to do with movement and exercise,’ says Sam.

One of the weekly sports activities is the mile around the school. Just a walk or a run, is also possible, around the buildings. Every day or every Friday. Then everyone joins in. Movement is highly motivated.

There is an officer for well being and there is an animal therapist. ‘Yes, we have animals. We will walk there in a minute. Do you want to see the Forest School too?’ Yes I want to see it all. Chickens and rabbits run around in a big cage. The children take care of the animals and clean the cages. The eggs are for the kitchen. We also pay a visit there. A couple of pupils have just started cooking with a supervisor. It looks relaxed and cosy. I immediately think of the cooking lessons at Acato. Some of our students now can prepare the lunch for the whole school, all by themselves. It is always nice and cosy in our kitchen. Like here.

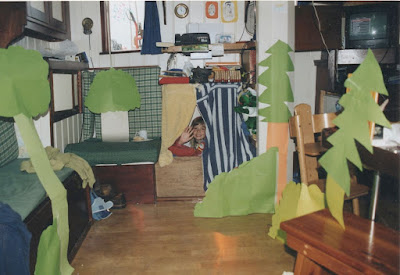

Behind the buildings, there is a large meadow. There is a piece fenced off. The Forest School. Trevor Wright is in charge here. He talks about his work. There is a workshop with tools for carpenting. Outside there is an herb garden. A large clearing has been set up for making a campfire. There are hammocks, there is a pond. I start talking about the hammocks. I had already seen beanbags in the classrooms. For faithful readers, my little trauma may be familiar. The criticism I received at my little school for drop out children: 'Everything is allowed there. I would be successful too! Haha, beanbags!’ ... The imbeciles!

Trevor reacts with passion. I don't remember his exact and warm words but it was more or less like this: 'No, these children are not lazy when they want to lie in the hammock. They are sometimes dead tired from everything and need that safe cocoon.’ My idea! He tells about their activities in the garden. In the summer, the animal will be next to his garden. And then all the outdoor activities will be brought together nicely.

This is also a school to leave your country for.

When we have finished the tour, Sam takes me to Louise Parkinson, the headteacher. In the Netherlands we don't have headteachers any more. Everyone is a Director. Even me! And that is really ridiculous.

Louise is a warm, enthusiastic woman with her roots in theatre. Her daughter is also autistic, she tells me somewhere in the conversation. She just about manages at school, 'although she does have troublesome moments.’

The Doucecroft School was founded in 1977 by a parents' organisation which would later be called Autism Anglia. This parent organisation was founded in 1970. The Doucecroft school is fully funded by the Regional Government. On average, the school receives about 70 thousand euros per year per child. (To compare: The special education in the Netherlands gets a maximum of € 17.000 per year per child. In addition, a lot of money is spent in the Netherlands on stand-alone treatments outside the schools that are intended to ensure that children do not drop out).

The local government pays Autism Anglia, which is also the owner of the buildings, for the various services. Education is one of their charities. The school rents the buildings from Autism Anglia. Autism Anglia pays the school for the education of the children. In the annual report this is called charity costs.

I ask Louise about the 'open doors' Sam told me about. Louise responds passionately. She has worked in several places, she says, where people with undesirable behavior were admitted. She noticed that somewhere in the past, fear of deviant behaviour had developed in those places. ‘Hide all knives! Someone might hurt himself or someone else!’ The reaction on more restrictions will be that the behaviour will only get worse. And that results again in stricter measures. She once worked in a place where, in the middle of the square, they had an isolation cell, to let overexcited residents cool down. She locked this cell and threw away the key. ‘As long as I'm working here, this cell will not be used', she had said. Louise also removed the restrictive measures. As a result the residents of that institution started behaving more normally again. ‘You have to treat people equally’, Louise says. ‘Doors should not be closed. That is unnatural.’

Children who attend the Doucecroft school stay there until they are 19. If a child starts at a young age, it has every chance to develop fully in a way that suits him.

This would not be possible in the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, coercion and pressure have completely overshot the mark. Suppose that in the Netherlands there would be something like the Doucecroft school, then a child would be sent back to regular (special) education as soon as he is doing well and feeling well again. In the Netherlands one assumes wrongly that a child has been repaired. They overlook the fact that the child feels good because he is in the right place, where he feels safe. If you take that away from him, things will go wrong again.

No, the Doucecroft school is not inclusive education, Louise admits, but they do everything they can to bring children into society. There are many activities outside. The week before, for instance, they took the whole school to the theatre in London.

Louise tells me that they cannot help all children. Some children cannot endure the space that is given to them. They need a different kind of setting, she explains to me.

There is another small side note. Each year, the school can accept only a few new pupils, while the demand is high. The school is the only one of its kind in the region. Louise is a bit frustrated about this. There is a reason to expand, she says, but at the moment there is no prospect of expansion.

There is much more to tell about the Doucecroft School. My advice is to visit the website.

What I take away from this lovely visit:

- Care and education under one roof.

- Classrooms with an extra quiet room.

- Hammocks and beanbags: an excellent idea!

- I would like to know how the funding of school and care is legally arranged in the UK.

- There are specific methods in the classrooms: I would like teachers from Acato to spend a few days at the Doucecroft school to experience the way they work.

- I like to dream about a school like this in the Netherlands for all children. An inclusive ‘Doucecroft-school’. What would such a school look like?

Reacties

Een reactie posten